Re:filtered #16: The limits of both data and intuition

Welcome to the 16th edition of my monthly newsletter on civic media opportunities in a moment of systemic disruption.

First, thank you to everyone who read and shared the last edition about the risks of clientelism in the media funding space, and what to do about it.

I have been slightly overwhelmed by the response and had to set aside a few days just to reply to messages. I didn't expect my writing could touch so many people.

Overall, the reactions fell into roughly three categories:

- "This is great wording for a new funding application!" (No! That wasn't the point.);

- It resonated with anger directed at others but without self-reflection;

- "You made me reflect on myself and what we collectively have done."

I'm most grateful for the third type, although it represented by far the smallest group; not because we're all cynical but perhaps also because so many of us don't see our agency.

My genuine hope for the future is that we replace the current performative funding-chasing treadmill with something that's more rooted in reality and focused on service.

If we're going to rebuild something meaningful, it has to start with honest self-reflection rather than recycled narratives aimed at securing the next drip-drip-drip grant.

To everyone who has newly subscribed: what you get here are monthly notes about our research work at Gazzetta and some kernels of hope for the journalism space more broadly.

More than a year ago, I started Gazzetta as a research lab to explore how international public media ventures could be reformed.

The opportunity at the time seemed enormous, with more than a billion dollars spent yearly by the United States and other liberal democracies on what was meant to be public service media globally, and that occasionally led to amazing reporting, greater accountability and some social change, but that largely focused on continued existence, abstract hubris, and the constant need to report some higher success metrics.

That now feels like trying to be an urban planner for Pompeii right when the Vesuvius erupted. With every passing month, the ecosystem appears to be further reduced to insignificance. Yet, the work we're still doing has given me far greater clarity on what journalism is and could be than I've had before.

These learnings might not always be immediately relevant to your work, but I hope you'll find some perhaps unexpected inspiration for navigating this moment of systemic disruption in media that affects us all regardless of how you have been paying your bills.

For instance, my colleague Rebecca just published another "work note" on our site about segmentation in audience research and mindset clustering to size market opportunities, which is just as promising for monetization as it is for publicly-funded media ventures.

I'll use an upcoming edition to write more about this if it's of interest. (Is it?)

The needs paradox

Over the past weeks, I've been wrestling with tensions that keep emerging in my conversations with media executives and researchers, and that often lingered between the lines in many conversations and panels at the International Journalism Festival in Perugia earlier this month:

The persistent tension between data and intuition in media. We struggle to reconcile analytical frameworks with creative instinct, functional information with emotional resonance, and content delivery with relationship building.

There are so many frameworks and concepts in this field, to quote Emil Cioran: "In all the edifice of thought, I have not found a category upon which to rest my head."

This intellectual tension reflects our struggle with defining media's purpose, and the inability to establish conceptual clarity. Something essential always seems to escape our categories.

What I've come to realize is that our industry's focus on delivering functional information misses what actually sustains many relationships people have with publishers (individual or organizations).

The publications that thrive aren't necessarily those with the best research or most informative content, but those that fulfill deeper psychological needs that audience research rarely captures.

At Gazzetta, we've seen this firsthand in a current project for security guards.

Initially, we focused solely on providing labor market information (the functional need). But what is now transforming our thinking was the discovery (in research) that many such workers had significant downtime during shifts and actively sought jobs with this feature.

This opened a two-fold opportunity: gathering data on which jobs offered more leisure time (more functional value) while also designing content specifically for those quiet hours that perhaps relaxes and entertains (emotional value).

The shift from asking "What information do they need?" to "How can we fit meaningfully into their lived experience?" changed our design approach.

Understanding this isn't about abandoning research but reconceptualizing what we're building for in the first place.

Here's a paradox: Some of the most successful media ventures (including the bad actors) don't intentionally serve any articulated functional need, yet they thrive. No research and strategy work, no OKRs or KPIs, just what seems to be refreshingly easy wunderkind magic.

Yes, some great publications thrive without any strategic blueprint beyond pursuing great storytelling. That's amazing, but to me it remains an unsatisfactory intellectual curiosity.

Does this invalidate this entire talk on need-based publishing strategies? Why research when some people and projects just seem to succeed? Is a journalism funder's job to look for the Wagners and Beethovens of journalism out there?

TL;DR: no, but it’s worth a closer look.

I recently joined a members' gathering of a thriving member-supported publication in New York. Some one hundred people took the time to gather in a midtown office space. Curiously, only about one in five participants raised their hands when asked about whether they had recently read that publication's work.

Yet, those other four in five members also showed up, paid for a ticket, and likely have renewed their subscriptions year after year not because they consistently read the articles, but because supporting the publication appears to fulfill something deeper.

I'd bet good money that a significant portion of subscribers to The Atlantic, De Correspondent, Krautreporter, Initium, or Meduza aren't religiously reading every word they publish. There is always a funnel but it's not a deterministic one that can be fully captured by metrics such as RFV (recency, frequency and volume) of content consumption.

They're probably subscribing to be part of something, to signal their values, to feel connected to a certain worldview.

The value isn't in the consumption of content, but in the emotional satisfaction of backing something that aligns with their values and identity. Content is just an expression of the product, it isn’t the product.

Do the editors of that publication fully take advantage of that? Just by looking in the mirror, I know that most trained reporters and editors will spend almost every additional dollar of revenue on additional reporting.

I was also struck by a conversation with an international broadcasting executive who mentioned that half their audience in Malaysia followed them for "aspirational" reasons.

Essentially, their research showed that these viewers sought to belong to something larger than themselves.

Imagine if that organization had actually embraced belonging as a part of their editorial strategy (not just marketing).

The growth potential was sitting right there, untapped.

Beyond deterministic thinking

A second paradox is a mismatch between research effort and ability to predict success. While some projects are researched to death literally and fail, others just thrive spontaneously. Why waste money then?

Here's an example from my professional life: A few years ago, my then team's research in Hungary identified widespread concerns around the quality of healthcare and education, exciting reporting opportunities rooted in civic utility.

The editorial colleagues then produced a few solid hospital and school related stories based on this insight, but those stories didn't perform particularly well. I got feedback that the "research didn't work."

This has become my go-to anecdote on a fundamental misunderstanding about how research translates into action, and how meeting needs translates to editorial success:

There is no deterministic connection between identified needs and audience response. People don't respond to content on an article-by-article basis. They respond to publications that consistently live and breathe their value proposition.

The research wasn't wrong, the deterministic assumptions were. Success isn't about individual story performance but about building a cohesive resonating experience that gradually becomes part of people's lives, over time.

And most importantly, we need to recognize that in venture design, there is no certainty.

There are good bets and bad bets. The fact that some uninformed bets worked out doesn't mean we should abandon research. (Unfortunately, algorithmic distribution has fooled us for a decade into thinking that some bad bets are great ones.)

What amazes me is that we've missed real opportunities in conceptualizing research.

Instead of building systems, roles, and processes that incrementally increase our odds – strategically, being mindful of emotional resonance and, tactically by learning from what resonates – we've used research to create false certainty around tactical data points. We chase comprehensive models pretending to capture all of reality, when such complete understanding is fundamentally impossible.

If we can reduce uncertainty and improve our odds even modestly, isn't that infinitely more valuable than chasing the mirage of complete predictability or surrendering entirely to editorial instinct?

Treating media as experience design

If I have an opportunity to work in a newsroom again, here are some learnings for me:

First, approach media as a venture that embraces both productive uncertainty and a focus on value: What tangible problems do people have? What real support can we offer? How can we maximize awareness of these benefits and measure genuine audience response?

For research: How can we increase the odds of success by understanding need, opportunity and receptivity, without falling into the trap of promising or expecting complete certainty?

Second, build small. The closure of the Houston Landing in Texas is another sad reminder that in media, it’s not "too big to fail" but "too big to thrive."

Perhaps the assumptions about critical mass are inverted in our industry? (The Rebooting has a great related conversation with The Ankler's Janice Min.)

If the core desirable experience isn't validated, scale (and expectations of scale) can become a liability. That's also a key learning of my time at Radio Free Europe.

(International) public media are largely stuck in a sunk-cost fallacy for existing "broadcasting" operations, and have a Quibi problem for most new ideas. The burden of justifying investments in the scale of millions risks dooming almost any venture from the start.

Third, aim for genuine emotional resonance (maybe even joy).

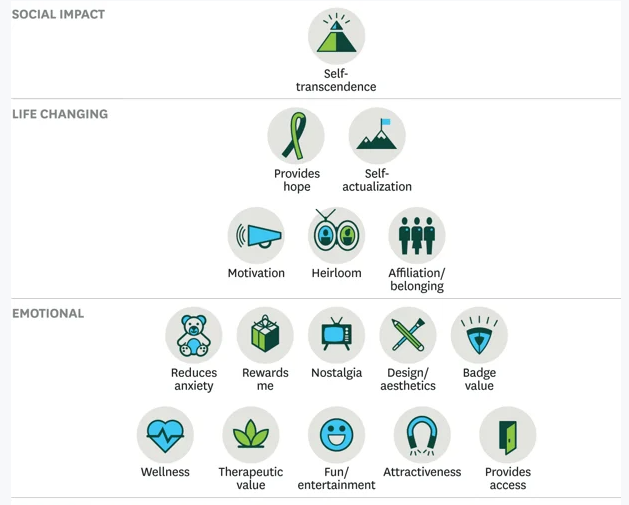

While there are taxonomies of emotional needs, we need more inspiring examples of media strategy that intentionally cultivate authentic emotional connection – not the fleeting dopamine hits of viral distractions, but the profound satisfaction that comes from a sense of shared exploration that helps make sense of one's world, rooted in one's lived experience.

This kind of joint discovery connects to the tangible realities people actually experience in their daily lives, not the distant procedural theater of institutional politics like press conferences, Brussels committees or U.S. Senate hearings.

I'm talking about stories that inform how you see your world in small but meaningful ways, that make you pause and reflect, that stay with you days later.

This kind of deep emotional engagement is far more powerful than even the most rigorous investigation.

We have a ton of theoretical knowledge (my favorite below) but few examples of how to transform these concepts into sustainable journalistic ventures that consistently deliver both informational and emotional value.

But what we really need are role models who demonstrate how to operationalize these insights in daily editorial practice.

Conceptually, I find the Bain Elements of Value model – a framework developed by consultancy Bain & Company that organizes consumer needs into a hierarchy building on Maslow's – very helpful for understanding some deeper motivations:

Affiliation/belonging: The international broadcasters' audience in Malaysia I mentioned wasn't just consuming news that aligned with their views; they were aspiring to join a community that had shared values and aspirations.

What would an editorial offering look like that doubles down on that?

Badge value: Media consumption as social currency. Knowing about certain stories or following specific outlets can position someone as informed, cultured, or politically aware within their social circles. The New Yorker tote bag and the red MAGA hat are walking billboards that signal one's cultural and intellectual affiliations.

Other psychological drivers the model doesn't address:

Identity reinforcement: Media that validates and strengthens our self-perception. Unlike belonging (which connects us to others), identity reinforcement is about confirming our individual sense of self – our values, beliefs, and worldview.

Moral clarity: Stories that reinforce one's sense of right and wrong, offering the comfort of moral certainty in a complex world. The extraordinary success of some partisan media isn't just about bias confirmation, it's about providing a coherent moral framework in a disorienting world.

Emotional regulation: Using media to manage one's emotional state – whether seeking anger as motivation for action, reassurance during uncertainty, or hope during difficult times.

Cognitive offloading: The relief of delegating complex thinking. In an overwhelming world, trusted media sources offer pre-digested analysis that reduces cognitive burden.

While functional utilities – the civic information needs around healthcare, education, transportation, etc. – feel so much more urgent and are much easier to test and build for, any such offering no matter how useful, still needs an emotional attachment to find resonance, over time.

The most revelatory reporting on healthcare or school systems will go unread and won't stand a chance of improving those systems without tapping into deeper psychological needs.

When someone in France follows Jordan Bardella on TikTok or in the U.S. listens to Bari Weiss' podcast, a blend of those emotional needs above are met by people who (I believe) meet them in bad faith.

Can we offer alternatives that don't fuel further ignorance, alienation and tribalism and that don't serve to further camouflage klepto/autocracy? We don't at our own peril.

It's way too risky to just hope for editorial wunderkinds, trust in editorial decision-making serendipity, and hope for liberal democracy to thus be maintained, developed, or regained. It certainly hasn’t worked so far.

A friend recently introduced me to the concept of "nested value" during a brainstorming call.

We thought of it as a media offering with a core functional benefit (like job opportunities) surrounded by concentric circles of additional value – emotional resonance, community connection, identity markers – that expand outward.

Such a rendering of needs feels more representative to how media actually works in practice than the Maslowian pyramid.

Returning to our security guard project I mentioned earlier, this nested value concept helped us rethink our approach.

Rather than just providing labor market information (the functional need at the core), we could be designing for the emotional context surrounding it.

A key insight came from recognizing that downtime during shifts wasn't just a fact about these jobs but an emotional state we could design for. We began exploring ways to systematically extract indicators from job descriptions and employer profiles that might reveal which security positions offer more downtime. This would add concrete functional value, but then how could we also fill that leisure time with relevant conversations that feel like a good use of these quiet hours?

This shift from seeing our audience purely as information consumers to understanding their complete emotional context completely changed this experiment's product strategy.

That doesn't just go for traditional journalism.

Take any publications' success with games and cooking verticals as an example:

Yes, they provide functional information (e.g. about recipes) but they also create experiences that fulfill deeper needs for mental stimulation, achievement, and daily ritual.

A crossword is a moment of focused calm and intellectual satisfaction in a chaotic world. A cooking app isn't just recipes; it's an invitation to creativity and nurturing one's family. The emotional payoff is probably as important, if not more than the functional utility.

To see more opportunities in these venture design approaches, we need a clearer understanding of the greater spectrum of services media provides beyond functional information delivery.

This requires developing a deeper understanding of the psychological dimensions that are often driving consumption decisions but perhaps often also remain largely unarticulated.

A challenge is that this approach is often dismissed as merely "marketing" of content. But what if the core product wasn't the content, but that social service of meeting psychological and social needs? What if the product was joy, clarity, peace of mind?

How can we get there? Here are some ideas that could work:

- Map the emotional landscape: Beyond demographic and behavioral data, can we study and understand more deeply the psychological needs driving a group's information consumption? And build for that too.

- Design for both dimensions simultaneously: Can we create products that intentionally address both functional and emotional needs, rather than treating the latter as optional "engagement" or marketing flourishes? I don't have any good examples here, if any come to mind, please send them my way.

- Measure emotional impact: Can we develop metrics beyond page views and read time that capture the psychological value people derive from a media product? I haven't seen but would be curious about results of the "how does this make you feel" smiley surveys (😠😔😊🤣) that may feel silly but are perhaps not so much.

- Train journalists in both domains: Can we help editors develop the social tools of conveying information beyond the delivering of facts? Perhaps we're also social workers, providing emotional services that make those facts meaningful. (New roles... another org chart conversation.)

All these questions are major reasons why individual creators now have a massive systemic advantage over traditional media organizations since they often deprive individual contributors of their unique individual identity.

But I have no doubt that media organizations that get this right and build on their competitive advantages including in terms of their internal distribution of labor can have an enormous competitive advantage.

So how might we practically apply these insights about emotional needs to build more resilient media ventures? If you're developing a media venture, I encourage you to ask these questions:

- What emotional or social appetites could you satisfy alongside informational value?

- How might you intentionally design for these less tangible needs?

- What small-scale experiments could validate your assumptions?

The most successful ventures I've seen aren't necessarily the ones with the clearest functional value proposition, or the most sophisticated research plan, or first-party audience data.

They're the ones that intuitively understand the emotional landscape of their community and design experiences that resonate on multiple levels. There's joy in belonging, there's surprise in shared discovery.

Can we artificially engineer editorial success with deterministic certainty in an environment we can fully capture through research? Of course not.

So should we rely on the innate instincts of a few chosen editors to sufficiently speak truth to power? Of course not.

But can we define an editorial strategy rooted in the lived experiences of real people? Hell, yes.

Can we work with the best editors to sharpen their intentionality and help them discover growth opportunities through greater empathy? Hell, yes.

Can we build media organizations around how they make people feel? Hell, yes.

Looking back

The International Journalism Festival in Perugia: I can see how invigorating it can be to see practitioners from elsewhere and forget one's own challenges in a beautiful setting for a few sunny spring days.

I sadly caught a bug on the second day and missed most of it. I'm gradually reaching out to people I was supposed to meet to catch up virtually in the coming weeks. If we were supposed to meet, I’d still love to meet online.

What made Perugia valuable was the cross-pollination of different journalism worlds.

It was noticeable how the three I happen to be part of brought their best attributes (and leaving their individual parochialisms at home):

- Colleagues working in American newsrooms and academia can bring their infectious entrepreneurial mindset, a welcome contrast to the often tiresome culture of personal branding that can dominate their world.

- Those from European media traditions get to share their deep commitment to civic values and public service, without the false comforts and the naïveté of hierarchical rigidity that so often limit innovation in their institutions.

- And colleagues working in East and Southeast Asian media contexts can bring an unrivaled down-to-earth pragmatism and camaraderie, that thrives when freed from the irrational paternalism that often characterizes the power dynamics in many media organizations there.

Seeing these strengths without their accompanying systemic limitations creates moments of genuine possibility – glimpses of what could be possible.

Looking ahead

In May, you'll find me back in D.C. and then at the Hacks/Hackers AI Summit in Baltimore to present some of our audience research work. It's going to be an early, more newsy iteration of a presentation at the Rosenfeld Designing with AI conference in June.

It's such a blessing as a learning experience, getting iterative feedback from folks working in completely different fields, from space travel (not kidding) to conversational design and app development. If you want to join, it's virtual and BOEHLER-DWAI2025 will give you a $75 discount.

I'll also be at the Lenfest News Philanthropy Summit in Philadelphia for some exciting workshops with friends.

I'm very grateful for these opportunities to learn, discuss ideas, and reconnect with colleagues I deeply value. As always, I'll share my slides in the upcoming editions of this newsletter.

Also a shoutout that the News Product Alliance Summit is still accepting pitches until May 9. Here's the pitch form. If I can help you brainstorm or support you in your pitch, let me know.

Here are my usual free slots. I am an introvert but it is a joy to meet new people, so don't feel shy to claim one even if we haven't met.

If all are taken, just message me on Signal (patrickb.01) or reply to this email, and we'll find some time.

I'm curious how this exploration of the false binary between research determinism and editorial genius resonates with your experience. If something here sparked a new thought about increasing your odds without chasing false certainty, do share your reflections with me (just hit reply). Consider sharing them publicly as well.

You have agency. You can help us all build better systems that improve our collective batting average. The most modest shifts in thinking and improvements in our success rate far outweigh either pretending we can predict everything or surrendering entirely to chance.

Until next month!