Re:filtered #23: Double servitude

Welcome to the 23rd edition of my monthly newsletter on journalism in a moment of systemic disruption.

Watching the Global Investigative Journalism Conference discourse from afar, I kept thinking about samurai in 1870s Japan. When their feudal stipends ended, thousands bemoaned lost honor. What they'd actually lost was status.

Some tried to become merchants. Most failed spectacularly. There's even a term for it: "shizoku no shōhō" (士族の商法): the samurai's business method. Too proud to bargain, too rigid to adapt, they opened shops that quickly went bankrupt.

We may be living through journalism's shizoku no shōhō moment.

Say this and you'll be accused of wanting ignorance, corruption and demagoguery to flourish.

Far from it! Questioning journalism's current forms isn't abandoning accountability. It's asking whether we're actually providing it, and trying to start more grounded conversations on building something that does, within the constraints we actually face.

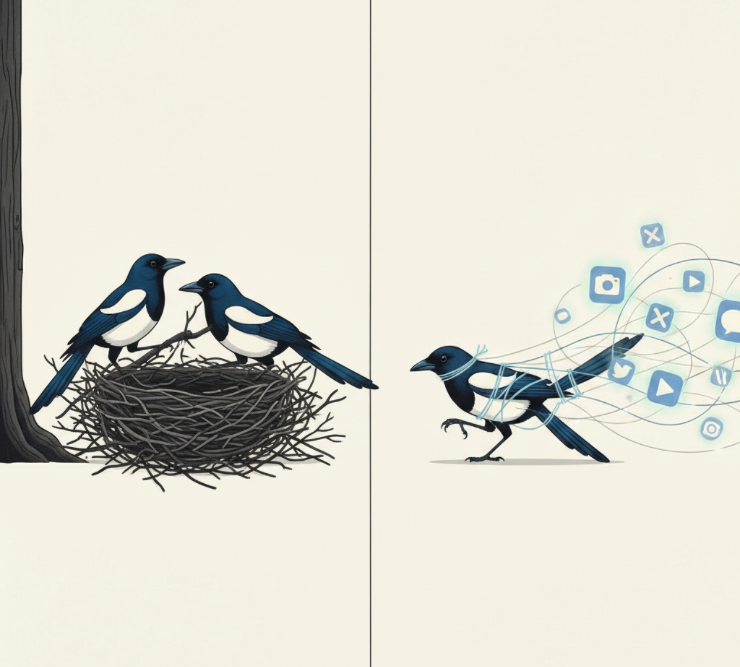

The journalism support complex sees the crisis and proposes its own hasty solution: abandoning old robes to try on new ones by pushing journalists into the creator economy and turning them into influencers.

Unfortunately, this is merely trading one form of samurai rigidity for another, a distinct, yet equally fruitless shizoku no shōhō.

Media business coach Corey Ford taught me something that originally came from IDEO: any successful product needs to be feasible, viable, and desirable. Pivoting to the creator economy doesn't mean we're meeting any of these conditions better.

It might just be a new way of failing the same tests.

Creator economy: from one master to two

Bobby Hilliard at Manychat, a service that caters to the creator economy and that we use in some research projects, had a sharp read on this earlier this month, in which he warns of not seeing this space for what it is: "platform labor dressed up as freedom." Note that this is coming from inside the house of the creator economy.

Creators are part of the "content supply chains" for landlords (platforms) who can evict them or destroy their income overnight. Hilliard breaks this down into two stark realities:

- The Audience Economy: This is the illusion most creators are trapped in. It’s the belief that "visibility equals stability" and that viral metrics define success. He calls this the "fancy showroom" where you grind for numbers that don't translate to leverage.

- The Access Economy: This is where the money actually is, but it’s a "velvet rope" economy defined by nepotism, PR lists, and backroom deals, not merit.

Both are unstable because they rely on rented land. To survive, you have to use them pragmatically while building toward infrastructure and relationships that are actually yours.

The journalism support space is actively pushing many into the Audience Economy, obsessing over reach and algorithmic discovery, while granting access to the lucky (sometimes entrenched, cynical or naive) few to their own small, emerging Access Economy of funding and connections.

The "trusted messenger" narrative is making this worse. The (unintentional) outcome has its precedent in international media funding: Journalists get paid (aka supported) to (implicitly) push aligned messages through their channels.

Just this month, I learned of yet another program recruiting creators to "do fact-checking work to engage young audiences." The intentions may be good, but the entire construct is samurai-thinking, starting from a misplaced sense of intellectual superiority, using organic-feeling formats to top-down push pre-approved narratives.

To quote Sarah Alvarez, founder of Outlier Media: "Narrative shift is not our job."

We escaped (often awful) newspaper gatekeepers only to now aspire to serve two masters at once: algorithms and advocacy funders? Double servitude is not empowerment.

No thanks. I don't care what the consultant class is selling this season.

We can navigate new realities without naivety and without recreating the same dysfunction in creator-economy packaging.

The work that isn't happening

The creator economy is real, it's massive, and it has long been shaping our lives. People build livelihoods there. But treating it as the starting point for media strategy is a trap.

So what's an alternative? It probably starts with seeing what's already there.

I've mentioned before how Megan Lucero and Cole Goins at the J+D Lab mapped how communities keep themselves informed.

In the framework they publicly shared this month, they identified eight distinct roles people play: Facilitating, Documenting, Commenting, Inquiring, Sensemaking, Amplifying, Navigating, Enabling.

The framework captures that no one is waiting for journalists. Parents document school board meetings. Municipal employees explain permit processes. Teenagers livestream protests.

They may not always do it "well" by the definitions of our craft, but that matters less than we think because they're doing it within the contexts of their actual lives, where we often aren't.

There's probably no such thing as a "low-information" person (bliss?). But many people are profoundly poorly informed. That's where journalistic skills can have a powerful role.

Try to map these community roles (documenting, inquiring, explaining, etc.) against civic information needs like education, healthcare, infrastructure, environment anywhere, and you'll see massive gaps. Information that's missing or unreliable.

Those gaps are meaningful opportunities.

A civic opportunity matrix

Picture a grid. Down the left: the eight civic needs (emergencies, health, education, transportation, economic opportunities, environment, civic life, public safety). Across the top: the eight community information roles.

Map any community and you'll see vibrant activity in some squares, unreliable information in others, and voids in many.

- Education: That parent Facebook group discussing school closures may be great at Amplifying education concerns. But no one is Sensemaking, i.e. analyzing whether closure patterns correlate with neighborhood income, comparing our district's decisions to others, or identifying the policy mechanisms that enable these choices.

- Healthcare: Plenty of people are Navigating insurance claims and sharing doctors. But no one is Inquiring into why certain procedures cost five times more at one hospital than another, Documenting the actual wait times across emergency rooms, or Sensemaking on which health outcomes actually improve with which interventions.

- Transportation: Riders constantly Amplify complaints about delays (a rite of passage for anyone living in New York City). But perhaps not enough of us are systematically Documenting patterns across routes, Inquiring into procurement contracts for maintenance, or Sensemaking on how our system's performance compares to other cities.

Finding the blank spaces

I'm not necessarily attached to the roles and issues, but I find this exercise helpful in understanding where journalistic skills could find a place in pretty much any context.

- Map a Beijing factory worker's experience: Everyone knows which factories pay better, but no one systematically documents which ones actually pay overtime as promised.

- Map a Buenos Aires university student's experience: Everyone knows the housing crisis is brutal, but no one investigates which landlords systematically reject students.

- Map a Filipino domestic worker's experience in Dubai: Workers share WhatsApp warnings about sponsors who confiscate passports, but no one documents which agencies honor contracts versus which ones change terms after arrival.

- Map a retired teacher's experience in Moldova: The bus schedule exists, but no one analyzes which routes actually run on time in winter, when medical appointments matter most, or which hospital is their best bet.

This isn't always glamorous work. It isn't meant to go "viral", but these are real jobs that are profoundly meaningful. They're information processing functions that need to happen for communities to make informed decisions.

This may sound dry. But there's enormous emotional work that can layer on top of functional service: helping people process loss and grief caused by these challenges, building a sense of solidarity to face them together, brainstorming ways forward, offering hope, or just finding moments to laugh about the absurdity of it all.

What filling gaps looks like

I'm often asked for examples. The Jersey Bee gave me a great one this month: foodpantries.jerseybee.org.

The innovation wasn't discovering that people go hungry. It was identifying a specific information processing failure. Directories existed as PDFs and spreadsheets. But no one was doing the Navigating role: calculating actual opening times, mapping locations to transit routes, calling to verify current information.

Simon Galperin and team became the information processor for that specific intersection of health/welfare needs and Navigating role.

The data behind this useful service could inspire investigations rooted in actual information needs. And on a psychological level, it could reveal where the need for solace and diversion may be greatest.

What this doesn't preclude

None of this means abandoning investigations or ignoring outrageous situations when you stumble onto them. A journalist documenting which temp agencies steal wages might uncover a criminal network. The difference is where you start.

Traditional editorial strategy starts with "what stories should we tell today?" and hopes or believes relevance follows (in part thanks to tactical optimizations in the creator economy).

A service-first approach starts with "what gaps exist in how people navigate their lives?" and lets investigations emerge from there.

Investigations rooted in identified community needs land differently than investigations done because someone thought they'd be important.

The former already has an audience waiting. The latter has to manufacture one. And when you do tell those stories, the emotional stakes are real because the information stakes were real first.

Teams beat solo creators every time

One more gripe about the creator economy: it sells a fantasy that you alone can be a media empire. Just hustle harder.

Nearly two years (!) of running Gazzetta have taught me the opposite. We're exponentially better together. When I hit a wall with research methodology, we're lucky to be able to turn to a researcher who always finds a solution (or proxy metric). When we struggle to articulate our findings, we're lucky to have an editor who can make sense of it all. Different skills multiply rather than dilute each other.

Look at 404 Media: four journalists who left corporate jobs and built something sustainable together. They didn't each become solo creators competing for scraps. They became a collective. Same with Zeteo or HugoDécrypte. These aren't legacy newsrooms. They're teams where complementary skills create something bigger than the sum.

Solo creators might spot a gap but lack the skills to fill it sustainably. Teams multiply capabilities. Different backgrounds spot different gaps. Complementary skills fill them properly.

For those ready to fund differently

Funders keep talking about how to "support news creators" (and sometimes desperately look for them). They're asking the wrong questions.

Stop funding people because they call themselves "news" creators. Stop funding influencers and "trusted messengers" because they have reach. We don't need them to advance "information integrity." They can't.

Instead, fund anyone who identifies and fills actual gaps. The opportunity matrix above can help you find them. Reach means nothing if it doesn't serve anyone but a platform. People with journalism skills are often well suited to fill these gaps but only if they're pointed at actual utility, not audience size.

Better yet, fund teams who do this, especially interdisciplinary ones: the librarian who understands information organization plus the parent who knows education systems plus the data analyst who can prove patterns. The nurse who sees health disparities plus the researcher who can document them plus the creator who can explain why they matter.

This works at any altitude:

- Building: which apartment units have recurring heating problems (health/safety)

- Neighborhood: how many units on your block are investment properties or short-term rentals, and what that's doing to rents (housing)

- City: how much public space goes to free parking versus transit infrastructure, and who benefits (transportation)

- State: the gap between what nursing homes tell families and what inspection records show (healthcare)

- National: following disaster relief money to see which communities rebuild and which wait years (civic institutions)

- International: which importers and retailers are passing tariff costs to consumers, and by how much (economic opportunity)

Such specificity keeps us from floating into abstractions about democracy or wasting time covering press conferences where nothing of consequence gets said.

The matrix forces the question: what information at this specific level could help people make better decisions in their lives?

What I'm still figuring out

I don't know how to resocialize journalists when I'm barely resocialized myself.

How do I convince anyone that maintaining a database of landlord violations matters when I still miss the adrenaline of what I used to do? When systematic information processing sounds boring and is nearly impossible to fundraise on?

I've sneaked into active conflicts, been tear gassed and threatened because I was socialized to believe that that hardship was a proxy for public service. What I actually did was mostly inform comfortable diplomats who, unlike me at the time, were safe in their offices, had vacations, insurance, and diplomatic immunity.

I wouldn't want to miss those experiences. The rush was real and the identity validation was comforting. Even now, making the case for food pantries information, part of me thinks: where's the adventure? Where's the recognition?

But I'd rather be useful and bored than thrilled and irrelevant. Most days, anyway.

We also need to think about funding differently. Yes, there's market failure in journalism. But maybe there are ways to build investment cases around information gaps, especially when they're tied to really expensive services like healthcare or education.

Could a hospital system fund systematic tracking of care quality if it helped them improve? Could a school district support documentation of resource allocation if it made their budgets more defensible? These aren't journalism grants. They're lateral business cases with civic utility built in.

And for philanthropy: wouldn't funding someone who fills a specific information gap be more useful than funding random acts of journalism of largely elite offspring wrapped in democracy rhetoric fed to social media slot machines?

Try this

Pick one civic need you encounter in your own life, like a school decision, a healthcare question, a neighborhood issue.

Then ask:

- Who's already doing information work here? Who's documenting, explaining, connecting people?

- What's being done badly? Where do rumors mix with facts? Where does Documenting feel more like surveillance? Where does Sensemaking sound like propaganda?

- Where are the voids? Is anyone investigating? Is anyone helping people navigate options? Is anyone making sense of what's happening over time?

These voids are opportunities. Not as one-off stories, but as ongoing services worth maintaining.

I'd love to hear what you find. (Let me know on Signal or by replying to this email.)

Looking back

A short trip to Berlin gave me a dose of hope. Against a depressing backdrop of naive and opportunistic bandwagoning around press freedom in Europe, conversations there on public interest technology and Europe's internet freedom role actually felt more informed and substantive than a year ago. I hope the momentum continues.

The News Product Alliance posted recordings of the NPA Summit panels, including mine, with friends, on AI in audience research.

On the Gazzetta site, our collaborator A. Feng shared her research comparing Western AI models with China's DeepSeek on labor rights knowledge.

DeepSeek contains highly contextualized knowledge about Chinese workers' daily constraints, once you tease it out through careful prompting. But it's wrapped in political controls that limit what users can actually access.

Western models face no such political restrictions. Yet they gave oblivious, impractical advice. Their output reflected Western assumptions and outdated information. Much like Facebook wasn't built to contend with racism in Myanmar a decade ago, they simply aren't built with these communities in mind.

As AI intermediates more of our information services, this gap really matters. Both systems fail to meet the actual needs of the people using them. One prioritizes political control. The other just never considered these use cases.

Better systems are possible and there's opportunity here. International models could be built to genuinely understand how people live under constraints the current systems ignore. Within these emerging systems, journalism practitioners could contribute by surfacing the information gaps the models miss.

I'll be presenting this research at a gathering at Columbia in New York in December, and we're publishing new findings in the coming weeks. More details soon.

And I published something that speaks directly to the measurement fantasies plaguing our industry: a slightly nerdy deep dive into why representative sampling makes very little sense in much of media research, and what we now do in our work instead.

I was looking for a way past standard research methods that are inadequate in dealing with systematic exclusion, when entire groups of people can't or won't respond to your surveys because of censorship, surveillance, or simple distrust. It's the same problem journalism faces when we pretend our YouTube subscribers represent "the public."

The traditional response is to gather more data from the same reachable pool and apply statistical weights, pretending we've solved the representation problem. This is false precision: tight confidence intervals around fundamentally biased estimates. It's the research equivalent of celebrating reach metrics while your actual community has moved on to WhatsApp groups you'll never see.

Our approach, which we have been applying to a project in Iran, flips this: instead of pretending we can see everyone, we get specific about who we can actually observe and why.

We segment by the actual constraints people face (e.g. blocked from app stores, under surveillance, using old devices) rather than demographics that explain nothing. Each segment gets its own rough estimate with wide, honest uncertainty bounds.

This connects directly to the creator economy delusion. Just as support organizations claim their chosen creators represent "youth engagement" or "community voices," they're extrapolating from whoever's visible on platforms to entire populations they've never actually studied. They mistake the people who algorithms surface for the people who could benefit from better information.

The methodology gets technical, but the principle is simple: stop pretending you understand populations you can't observe. But don't give up either. Start from what you can actually verify. Build outward carefully. Be honest about where knowledge ends and assumptions begin.

I'll be presenting this methodology at SplinterCon in Paris in early December, with our great partners at ASL19.

Looking ahead

In addition to Paris, I'll also get to be back in Berlin briefly next month for workshops. If you're there, let me know. At the end of the year, you'll hear from me again with plans and news for an exciting new year.

I've tried here to add nuance to the stampede toward creators. The opportunity is real. The mistake is treating the creator economy as a destination rather than a channel. Broadcasting failed. But swapping institutional dysfunction for atomized individuals chasing platform pennies is just regression in trendier packaging.

Maybe we're not witnessing journalism's death but its (re)scattering across communities. The transition is bumpy. But there are opportunities for teams of people with journalistic skills, not lone creators chasing algorithms, but groups with complementary capabilities keeping each other and their social circles informed.

Most of the samurai who tried to preserve their identity while entering commerce failed: shizoku no shōhō. But a few transformed completely.

Iwasaki Yatarō, born into a debt-ridden samurai family, acquired his domain's ships when the feudal system collapsed and built Mitsubishi by crushing competitors with the same strategic thinking he'd once applied to warfare.

Godai Tomoatsu saw the industrial revolution firsthand in Manchester and came home to transform Osaka from a sleepy merchant town into Japan's commercial heart.

They succeeded not by being better samurai, but by letting go of what didn't work while keeping skills that still had utility. Their literacy, discipline, strategic thinking, and networks set them up for success. They melted down their swords and built railways.

But there's also a quieter model. A samurai teaching village children mathematics wasn't betraying his craft. He was applying discipline and bringing literacy where they were beneficial. Maybe his students built modern Japan, or maybe they just understood their harvests better.

Thank you for reading. If you have a moment, let me know your thoughts!

See you next month.